![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Judge Institute of Management Studies, Cambridge University, England

Click once on the pictures to enlarge them to full screen size and bring up the Captions

THE BRIDE STRIPPED BARE

The best way to understand the Judge Institute building is to think of it as a fragment of some giant Metropolis unaccountably marooned in a little English country town. The best way to come upon it is to enter the gate of Downing College. Walking past Quinlan Terry's brand,new Doric Library portico and entering the wide campus lawns of the College, set with Classical stone pavilions in the manner abandoned in Britain after the French Revolution, one comes upon a strange and unnerving sight. A great polychromatic temple looms in the sky to the West.

In fact it may not unnerve the inhabitants of Downing, for they already inhabit Greek buildings, even if they are the pale uncoloured ghosts resurrected by the Renaissance. Those who need to acquire an intellectual handle on the Judge buildings are the great majority in the University who accept the myth projected by Cambridge's Post '45 War Architecture. This is that of a country town inhabited by a community of Rustic Mechanicals with a facility for invention such that it leads to rich crops of Nobel Prizes and the No. 1 slot in the Island Albion League of Academicals. The Judge strips the pretensions from the hyperbolic modesty of this rustic paradigm and projects at least one of the modern Institutions of the University at the metropolitan, national and, indeed, global scale of its real ambition. In doing so the Judge strips the veil of that unassuming modesty, which is the unnerving prerogative of real aristocrats, from this fragment of the University and reveals it as it, and its older fellows have been for many centuries: a player on the global stage.

STOLEN CLOTHES

The oddity of the actual event is that this 'stripping off' of the Post-war pretence of an Proletarian humilitude was brought about not by any very direct Architectural assault upon the prevailing paradigm, but by filching the clothes of a mid 19C Monument, not of Gown, but of Town. Nor was this a brave and honest decision of the University. It was a predicament forced upon them by some of the Historians of Art at the University. For it was they (the 'Gowned) who encouraged English Heritage (for the benefit of the 'Town'), to 'list' the giant façade of the City Hospital for legal preservation.

THE 'TABOO-BREAKERS'.

Two Agents now stepped into a situation which had, by this act, passed entirely beyond the iconic vocabulary of the 'Rustic Paradigm' under whose aegis laboured the the Agencies established to house the University's Faculties. They were the two financial Donors of the new building, Paul (now Sir) Judge and the Honourable Simon Sainsbury. They were determined to abolish the prevaling 'Cambridge-style' lifespace disguise of a politically defunct 'welfare culture' and institute something more honestly ambitious and brilliant. This is why they appointed my firm, and not one which was accustomed to working with the University Surveyors. For it must be said that these Agents, proposed by the University to choose their Architects as well as control their designs, in the early 1990's, were as entirely free of Architectural culture as the grey skies of the Fens.

The Donors, along with their adviser, Colin Amery, chose JOA as their Architect, and they entirely, and directly, controlled every aspect of the design. The Judge Faculty, themselves, interacted creatively. But the University, as such, did nothing except keep the Minutes and sign the Contracts. Their technical, and managerial Agents made not one single contribution to the design and specification of the project. It was an object lesson in the extreme lengths to which it has been necessary to wean even the highest levels of the British from their dismally institutionalised Welfare Culture, with its cult of dumbed down proletarianism, iconic illiteracy and early-retirement pensionnareism.

MODERN MONUMENTS

Any building, today, which means not necessarily a major one, for a major Institution, is free to use itself, especially on its interior (where it affect no-one but its own 'citizens'), to project a futuristic view that envisages (according to them, at least) a quantum-leap in lifespace-culture. The Judge began by being a great façade that looked outwards across a forecourt. It was the opposite of the typically inward-looking courtyarded College. This was because its building originally enjoyed a civic role of great importance, encompassing physical life and death. It was obvious that the Judge building could be the occasion for a major demonstration of certain radical new ideas in lifespace-design. The whole project went forward on this basis, serving both the particular interests of the Institution together with the larger project of a radically re-engineered lifespace culture in general - just as does any legitimate Cambridge research project. No one invents new intellectual paradigms to be consumed merely within a cycle ride of the Cam, so why should Architecture?

THE AGONIES OF COMING CLEAN

The advent of directly-donated money destroyed the long-established relation of Oxbridge to Whitehall that ensured that State funds, lost from their individual sources into the cosy bureacracies of Whitehall, travelled quietly and unobtrusively up from the Department of Education and Science to diverse Faculties. These made sure to house themselves in patently illiterate sheds which could never be recognised as what they were, the lifespace of an uniquely gifted, hard-working class of intellectuals whose ideas were well out of the normal reach of the middle class, let alone the masses. In this way the intelligentsia, such as they were, disguised themselves from the envious eyes of the less gifted and less ambitous.

AND THE EASE OF STAYING GRUBBY

The Judge, for a brief moment, attempted to destroy this dissimulation. It was the best chance that the beleagured supporters of the 'high culture' had to publicly testify to the depth and range of their complex intellectuality (well, in fact, only on a building's interior). But they ran away from it and cowered behind their old disguise of 'humble poverty'. A building of patent iconic richness, especially one funded by real, individual, nameable, 'millionaires' was not popular with the University. And it was not only the University's Surveyors who chafed under their new subjection to cultured and wealthy Tycoon's along with their London Design Teams. The Dons and Fellows also disliked being exposed as being possessed of recherche cultural qualities &endash; more especially as they had no secure means of judging whether this 'difference' was properly mediated by an Architectural Medium whose dominant, and spuriously 'local', qualities, since 1945, had been to deny itself capable of any rhetoric except that of the 'honest, proletarian, woodworker and bricklayer'. This was the so-called 'Cambridge Style', as it was known from the 1960's onwards. It was the style JOA were hired to defy and overcome.

It was, no doubt , inevitable (for that is what happened) that this attempt to demonstrate the superiority of a modernised 'high culture' over either the dumb frauds of Arte Povera, or the more extrovert puerilities of 'Pop-Mechanics', should ultimately be thwarted by the intellectual confusion and public pusillanimity of the Establishment. It was also, no doubt inevitable that this self-inflicted class-cultural suicide would be followed by redoubled attempts at the dissumulation of Cambridge's real stutus and ambition. These retreats were enthusiastically aided by Professionals, shocked by the history of the 1980's into the recognition of the inability of their contemporary Architectural Medium to mediate anything more intellectually sophisticated than the plodding pragmatism of the Welfare aesthetic with which the University Administrators still remained most comfortable. Cambridge relapsed back into the rustic vocabulary of - turf roofs, shade-louvres, vent-cowls and sundry other fashionably agricultural devices more suited to the pedagogy of milking-cows than the most brilliant young minds of Britain.

IN A NUTSHELL

The Judge Institute of Management Studies was established

in 1990 from the teaching work previously carried out in the

Cambridge University Engineering Department. In 1991 a

design competition was held for converting the Old

Addenbrookes Hospital, located on Trumpington Street close

to the city centre and unused for over 10 years into a

purpose built facility for the new institute.

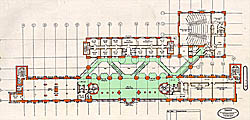

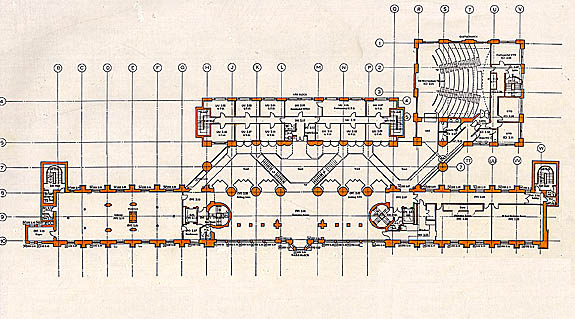

We converted the listed Ward Blocks and Arcades and rebuilt

the Central block of the Old Addenbrooke's Cambridge City

Hospital into the library, common room, seminar rooms,

computer teaching rooms, seminar boxes, A.V. meeting rooms,

the main hall of the new institute, and space for

expansion

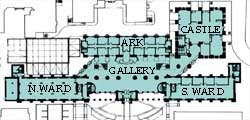

We added three new buildings:

- the Ark, containing Professor's and Research graduates Rooms, and the Administration,

- the Castle, containing the Biochemical Campus break-bulk facility, the Main Auditorium and the Debating Room together with the MBA teaching spaces and rooms,

- the Gallery, an 80 feet (24.5m) high space containing the seminar boxes, the multi-level circulation routes, the social stair, and part of the hall.

Exterior

It had been decided to remove the early 20C top floor,

which everyone found ugly. But all that it needed was a big

new cornice scaled to the whole facade, and a dado to bring

it down in scale itself to that of an 'Attic' floor, thus

giving the faculty valuable expansion space.

The 20C floor is preserved, and civilised, by being reborn

upon a bed of wavy leaves.

The 19C bricks and terracotta have been cleaned and restored

, but not too highly.

The new work is clad in brick and acid-etched polychrome

concrete, including blitzcrete " (our name for "dutch

"concrete made from crushed brick) and "doodlecrete" (our

name for inlaid concrete made with rubber moulds).

Whilst most people see the building from the Trumpington

Street side, the view from the other side is as impressive,

especially when viewed from the centre of Downing College,

where the roof of the Gallery (nearly as tall as Kings

College Chapel) floats ethereally above the Ark, the Castle

and the neo-classical buildings in the foreground.

GREEN CREDENTIALS

We call the Judge Institute complex a "Brookestead

Block®"', after Addenbrookes and the ideas underlying

the new design. It is made of separate buildings that embody

a "Republic of

the Valley®" between their sides. This tiered

"valley" gives an Institution a "natural" space in which to

'embody' its society and hence a 'green' foundation..

Technically, the building addresses 'green issues' because

it:

1. is in the centre of a

beautiful old Mediaeval city.

2. introduces "synthetic

masonry" to Architecture of the highest quality, avoiding

the need to use rare natural cladding materials..

3. Is designed to attract the

business corporate community but has hardly any car parking.

It has cycle parking for 250 units.

4. re-uses a huge old civic

building: the City Hospital, by modernising it without

compromising with any repro-styles.

5. keeps its rooms well

day-lit.

6. uses no A/C on a dense urban

site by employing the "Solar

Spiral" making large rooms very high and a using solid

roof over the central atrium. Projecting fins also reduce

solar gain through windows.

7. maximises the use of stairs,

which is beneficial for health, by keeping floor to floor

heights (8'6") very low indeed.

8. uses no propped floors or

suspended ceilings, exposing the thermal mass of the

concrete floors.

9. Creates a new kind of

"landscaped" work-space for the computerised work

culture.

10. Introduces radically new

ways of organising building services and architecture: the

"Working Column" and the "Working Beam", both parts of the

"Sixth Order",

which simplify maintenance and 'cost in use'.

11. Introduces the

roof

garden as an integral part of the workspace, concept and

function.

12. Went half way to the ultimate function of the "Sixth Order", which was to return Architecture to her place as 'Mother of the Arts" by surface-scripting the giant Service columns with the 'Video-Masonry of the "Talking Order" . This would have made the columns of the Judge Institute not only the most beautiful columns in Britain but the most intellectually legible .

£100,000.00 was given to JOA, to use for this purpose, by one of JOA's previous, and most loyal, Benefactors and Clients. The groundbreaking designs and technology were made available by JOA. However, there was an attempt to appropriate the 'monoprinting' technology by a 'share take-over' from the Donors of the Judge Institute itself - in case it might become a marketeable process and earn the Business School an income. This act of 'business opportunism' was exacted upon a benefaction donated specifically to aid the long-running Architectural project of JOA. The £100,000 benefaction was demanded back by JOA's Benefactor and returned, with interest, by the University. It was the first time, in the 600-year history of Cambridge, that a donation had ever been returned by the University .

To actually succeed in this ambition to inscribe an interior which would, in some small measure, reflect the intellectual quality of its users, I had to leave Cambridge, England, with its terror-struck fear of publicly testifying to its elevated self-esteem, and travel to a Faculty of Engineering in Houston, Texas. It was there, 4,500 miles away from tired, fearful, highly-educated Europe, still cowed before the ghost of an illiterate proletariat that Adolf Loos, and all of his incompetent descendants, were too uninventive to know how to lead, that I found a culture confident enough to demonstrate its legitimate ambitions. Thus it was that this 'final stage' of a total 'Iconic Engineering' was achieved in Duncan Hall, of Rice University, Houston, Texas.

In the end, Cambridge got its Business School. The Judge has a hugely cultivated building, with a dense intellectual cargo, that makes very sure that none of this rich 'high-culture' shows. Internally, its colour scheme has, as it has been described to me by others, the qualities of a "folkloric nursery". To begin to understand what it should have looked like one must go to Texas - a journey that ensures that no one in Europe will ever know the truth. An early cohort of Judge graduate students, of the customarily polycultural mix, were polled by one of their number, a Greek girl. Her statistics, perhaps surprisingly, reported that the Students felt that the central space, the common room, was 'cold'. This was not a registration on their corporal thermometer. It was clear, from her report, that, although they knew nothing of the original decorative ambitions of the Judge, they were registering that decision, taken late in the history of its construction, to erase any overt and patent signs that the Judge was a building with a warm and vital Architectural culture.

Another index of the cultural values which finally triumphed at the Judge was the peculiar fate of the roof garden. It is paved in cheap cement slabs surrounded by builder's gravel. Yet, under this, there is the most expensive roof specification of its day, an Erisco-Bauder 'green roof'. This has water-proofing on both sides of the insulation as well as a a layer of copper to prevent root penetration. It needed only turfing to complete. The roof is surrounded by huge pre-cast concrete planters that would easily accommodate 20'0" (6M) high trees, let alone more modest plants. Each of these planters cost, in toto, some £9,000 to get into the architectural prominence that they obtain. Each planter is grooved to accommodate the pipe of an automatic watering system. One of the hollow columns along one side of the roof was planned to accommodate the header tank and valves.

The roof garden is actually only half way up this building and is overlooked by two floors of Seminar boxes across the Atrium. It faces East, but it is protected from the wind on all sides. Yet it still manages a slice of view over the greenery of Downing College.

Late in the day the pipes, tank, turf and plants were cut. Virtually no money was saved. The argument was that the plants would need looking after and the grass would have to be cut. Even the secretaries to the Judge offered to look after the plants. Even now, all that anyone has to do to have a beautiful roof garden on the Ark block is to lift the dirty cement paviors, trash them and put down turf. All that anyone has to do to have trees in the planters is to put cheap fibreglass domestic water-tanks, as earth-filled planters, inside the very expensive black concrete ones.

But no, just as the interior had to be subliterate, the garden had to be made of cement slabs and the planters filled with rusting coca-cola cans. Business is a serious business. It is about making money. It should not be mistaken for anything leading to an improved standard of actually living. What would shareholders think of a place in which the workers actually enjoyed working when they should have been out buying and consuming? Why do we trouble to have business schools, in a serious University, if their ethos is so socially sterile?

To learn more of the 'hidden' Architectural culture 'built-into' the Judge click on the yellow square of the 'Brookstead Block' below (for a really long read), or, for something shorter, with pictures, on "Talking Order" .

INDEX OF ILLUSTRATIONS

THE GALLERY: "SEMINAR-BALCONIES"

THE GALLERY: "ENTERING THE CASTLE"

THE "WARD BLOCKS AND 19C FACADE"

THE GALLERY- "SEMINAR BALCONIES"

THE "WARD BLOCKS AND 19C FACADE TOPPED BY A NEW CORNICE"

the

AWARDS

Civic Trust Award

Brick Development Association Special Award

RIBA Regional Award

David Urwin Award "Best Building of the Decade"

Lighting Award

Paint Award

Joinery Award

AREA: 9,000 sq.m.,

Cost £M 11.0

Timetable.

Project Competition: Dec 1990.

Design commenced: April 1991.

Working Drawings commenced: July 1992.

Planning Permission received: November 1992.

Tenders issued: December 1992.

Contract commenced: April 1993.

Move-in: Sept 1995.

Official opening By HM The Queen March 1996

CREDITS:

Client: Cambridge University .

Principal Donors: Paul Judge and the Sainsbury Monument

Trust.

Architects: John Outram Associates

Structural Engineering Consultant: Felix Samuely

Partnership.

Mechanical and Electrical engineering: Max Fordham

Partners.

Cost Consultants: Davis Langdon and Everest (Cambridge).

Landscape design Consultants: Holden and Liversedge.

Main Contractor: Laing (Eastern) Ltd.

Click here for Judge Institute of Management Studies links

* JOA can be reached by E-Mail at anthony@johnoutram.com , by telephone on +44 (0)207 262 4862 or by fax on +44 (0)207 706 3804. We also have an ISDN number : +44 (0)207 262 6294.